AI feels like 1999 all over again

Last week, I spent two days with an old friend. We’ve known each other for fifteen years. He’s curious, a bit of a geek, but not “in tech.” He doesn’t use GPT. His wife doesn’t either. They’ve heard of AI the way you hear of a new restaurant: name recognition, no bookings.

We talked, we cooked, we compared notes on work. At some point, I realized we were living on different planets. Not values. Toolchains.

He does great work. But AI just… isn’t part of his day. Meanwhile, I use it constantly: as a writing partner for emails, a sounding board for product decisions, a junior PM, a marketing intern who never sleeps. It’s not magic. It’s just leverage. And it reminds me of when I got internet access twenty-five years ago and people said, “Why would you need that every day?”

Two decades later, we answer that question by reflex, usually from a phone.

I don’t say this to flex. I say it because the gap is already visible.

If I compare my work today to two years ago, I’m doing two to three times more with better output. Same hours. Less context switching. I can hold more of Mergify’s product in my head, ship faster, and still write the marketing we used to split across two people. I wouldn’t claim I replace a whole team (let’s keep our illusions calibrated) but one founder plus AI now feels like one founder plus a sharp apprentice who learns absurdly fast.

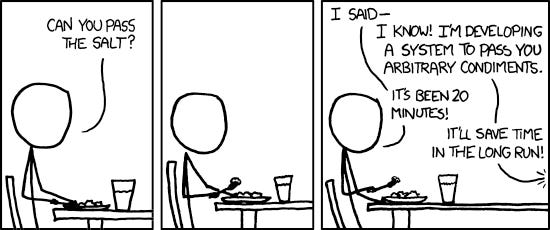

And I’m still only scratching the surface. There are tasks I should automate that I haven’t, because of the classic XKCD curve: spending an hour to save a minute. The ROI is real; the overhead is too. It will get smoothed out, like everything else that starts out lumpy.

What’s striking is not just the productivity jump. It’s the new behavioral divide. Twenty years ago the divide was access: who had broadband and who didn’t. Today the divide is adoption: who’s willing to put these systems in the loop every day, and who keeps them at arm’s length.

Same laptop. Same calendar. Wildly different output.

This isn’t about “AI replacing jobs.” It’s about AI reorganizing work around people who are willing to collaborate with it. The difference between “I don’t see the point” and “this is in my daily loop” already compounds in quiet ways:

The email you write in 7 minutes instead of 27.

The product spec with five explored options instead of two.

The marketing page that results from testing three angles instead of arguing for one.

The code you ship because the blank page wasn’t blank.

Multiply that by days, then by years. That is how careers and companies diverge.

Of course, there are limits. AI isn’t judgment. It won’t hold your ethics, defend your taste, or choose your strategy. You still have to decide what “good” means, define constraints, and call the trade-offs. If you outsource your thinking, you don’t get leverage: you get noise.

But if you keep the steering wheel, the car is very fast.

There’s also a cultural point I didn’t expect: the stigma of using help. Some people still think “real work” means doing everything yourself. Same energy as hand-writing HTML in 2003 to prove you’re serious.

This reminds me of the latest post from Jean de La Rochebrochard where he talked about how French people are all about crafting. No wonder AI adoption is going to be a long road here.

But the craft isn’t in suffering; it’s in outcomes. Tools are honest if your goals are.

I don’t know precisely what the next twenty years look like. I do see the pattern. Early on, new technology looks optional, even irrelevant. Then someone quietly uses it to do three times more with the same time. Then we call it table stakes. The people who adopted early won’t be smarter; they’ll just have trained their reflexes sooner.

If you’re already all-in, you don’t need my sermon. If you’re AI-curious but unconvinced, try this: pick one workflow that hurts: a weekly email, a product spec, a marketing outline. Put an AI in the loop for a week. Not as a demo. As a colleague. Give it context. Ask for alternatives, not answers. Keep the steering wheel.

If after seven days it doesn’t save you time and improve your output, fine: ignore it for another year. But my bet is you’ll feel the old dial-up-to-broadband moment: once you touch the speed, it’s hard to go back.

Back in Toulouse, my friend and I didn’t resolve anything. We just noticed the split. Same age. Same curiosity. Different daily habits. Twenty-five years ago the web felt optional right up until it didn’t. I think we’re there again. The storm isn’t coming. We’re already in the rain. You can stay dry for a while. Or you can learn to dance in it.